“You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t force it to drink.” Symbolically, this little saying summarizes the huge relationship between religion and spiritual transformation. The horse is the human spirit. The one who leads the horse to water is religion. And the water is Olódùmarè’s wisdom. So at its best, Yorùbá religion recreates the conditions in which original discoveries were made about spiritual transformation. The Holy Odù ÌrosùnÒyekú says, “Olomo, please transform destiny for the better. Afedefeyo, the multi-linguist, please transform the world for good, so that the world is not destroyed.”[1]Olomo and Afedefeyo are appellations of Òrunmìlà, the owner of the sacred Ifá oracle, which is the word of Olódùmarè. Consequently, throughAssessment (Ifá divination), Transformative work (sacrifices), and Sustainable practices (eewo), Yoruba religion intends to facilitate spiritual transformation. But practicing the religion does not guarantee spiritual transformation. In order to be actually transformed, your spirit must acknowledge, accept and assimilate the change. This is the psychology of meaningful change. It says that, in order to experience meaningful change, an individual needs to master two main types of activities: one set of activities emphasizes using Assessment, Transformative work and Sustainable practices (ATS) to create a framework for focused spiritual development. The second set of activities emphasizes adopting òrìsà lifestyle agreements that gradually enable you to live the medicine that facilitates spiritual transformation. If you’re like most contemporary American urbanites, the first step to living the medicine is to overcome the legacy of Sigmund Freud. In case you don’t know, Freud is the father of psychoanalysis, which has been used to reveal the secret desires of the masses. For over fifty years now, these secret desires – mostly of a sexual and violent nature – have been exploited by the political and marketing industries to condition the American population to seek all forms of personal fulfillment through acts of consumption. So, today when you want to fulfill your masculine identity, you buy something like a car or a weapon. Likewise, if you want to accentuate your femininity, you buy something else, like a dress or a day at the spa. If you want to assert your individuality, you buy something like a tattoo. And when you need to affirm your deep relationship with someone, you buy something like a promise ring. A growing movement called shopper activism even empowers you to “vote with your dollars” when you want to fulfill your civic duties. Naturally then, when you want to experience spiritual fulfillment you buy something, like a book or a crystal. This is especially significant to the American practitioner of Yorùbá religion because the religion abounds with innumerable sacred objects, countless rituals, elaborate ceremonies, and myriad initiations. This vast material complexity, coupled with a culture of consumerism is a dangerous cocktail because in the consumer world, the market tells you that value is determined by cost; the more something costs the more valuable it is. Spiritual transformation, however, cannot be bought. It must be lived. Of course, this is not exclusive to òrìsà lifestyle. Consider, for example, that nobody would even consider paying ten thousand dollars to get baptized! Everyone knows that admission to heaven is not going to be influenced by how much you paid to be baptized, who performed the ceremony or where it was performed. The primary reason anyone would pay that much for òrìsà initiation is because of what he or she perceives he or she will get in exchange. This is what I call the psychology of fabricated needs and superficial change. The psychology of fabricated needs and superficial change represents a serious challenge to our ability to live the medicine because it inhibits our ability to distinguish between òrìsà and an object of similar cost, like a BMW. And in case you don’t know for sure, the difference between òrìsà and BMW is the true value of each. Consider this question, if you will; “What’s the value of a good idea?” When you include some of the good ideas of our time, like the internet, civil rights and sustainability it becomes blatantly clear that the value of a single idea. It yields benefits over and over, throughout time. So it is with the message of Ifá. What the diviner shares with the client far exceeds the cost. Take, for example, the man who comes to me – his babláwo – for ATS because his wife mistreats him. In the initial Assessment, Ifá says his wife is both bewitched AND that she is his chosen wife from heaven; that is, she alone will bring him into contact with his destiny. Ifá says that hisTransformative work will include a series of sacrifices to appease the powerful beings of the night. And for his Sustainable practices, Ifá says that everyday he must use a ritually prepared soap and exercise deep patience. He adheres to Ifá’s instructions and is rewarded with a happy home. Within months, the man is genuinely happy with his wife for the first time in years. It cost him thousands of dollars. But if you ask him, he will tell you that his happiness is priceless and the work was worth every penny. This represents the arrangement of a single òrìsà lifestyle agreement that enabled a man to live the medicine that healed a particular area of his life. If he wishes to see the blessings expand and take root in other areas, he must adhere to increasingly deeper and more intense cycles of ATS. Gradually, he will experience spiritual transformation. December 31, 2012  Alexandra came to me for Ifá divination because of a dream she had had a couple of days before. It was not a nightmare. But she knew it was charged with deep spiritual significance. She dreamt of herself, asleep in her actual bed. And in the dream she was awakened by a presence. Without speaking, this presence wanted Alexandra to look at it. When she looked over her shoulder, Alexandra saw an ancient Black woman, with a very soft looking face, who radiated bluish-lavender light. The intensity of her power was matched only by her gentleness. So when the ancient mother demanded that she come to her, Alexandra understood the urgency but was not at all afraid. As she recounted the dream to me, her eyes glistened with awe. Finally, she asked the million dollar question, “Who was she, baba?” And of course, I was tempted to fill in the blanks with my own impressions, based on the dream symbolism. But, in keeping with best practices of the Jungian approach, I deferred to her personal wisdom and asked a few more penetrating questions, probing for more and more details that would allow her to connect the dots herself. Once we had exhausted her memory and she had reached a deeper connection to what the dream meant to her, I knew we were ready to ask Ifá. Thanks to Olódùmarè, the message affirmed her own assessment, and we were made privy to the ancestral context for what the dream meant and why she had experienced it at that particular point in her life. How Does it Work? The Yoruba say “ala ko ni eri” which means that “dreams have no witness.” They play themselves out in the dreamscape, where the individual is at one with raw consciousness. So, how is it possible that the myths of Ifá divination can speak directly to a person’s condition to the point of even seeing into her dreams? Part of the answer is found in the relationship between thepersonal unconscious and the collective unconscious. The personal unconscious is the medium of unique individual experience. It is limited and defined by what you touch, taste, smell, see, hear, feel (emotionally) and think. Meanwhile, the collective unconscious can be understood as a two-part pool of all human experience. In part one, we have the collection of cultural experiences, which explains why African people across the Continent and around the world enjoy a shared worldview and cultural expression. This is what Robert Farris Thompson is alluding to when he says that one might conclude that much of the world’s music has been influenced by the flash of the spirit of a certain people specially armed with improvisatory drive and brilliance. That’s a result of the African collective unconscious. In part two, there is the aggregate of all cultural experiences, which explains why it’s so easy to discover identical psychic motifs in the mythologies of peoples who have never made contact with one another. The hero and the witch, show up in the myths and folklore of practically all peoples. Similarly, falling and flying are equally universal motifs in the dreams of all peoples. That’s the result of the universal collective unconscious. Jung says that the collective unconscious is a “psychic system of a collective, universal, and impersonal nature which is identical in all individuals. This collective unconscious does not develop individually but is inherited. It consists of pre-existent forms, the archetypes, which can only become conscious secondarily and which give definite form to certain psychic contents.” What Jung calls archetypes the babláwo calls the Holy Odù. The Holy Odù speak to the origins, of the natural world and the human expression of it. Our laws, arts and customs are thus rooted in metaphysical principles that can only be known through the unconscious mind (i.e., the human soul). November 2011 Kan to gbe nu e no gbe kan do

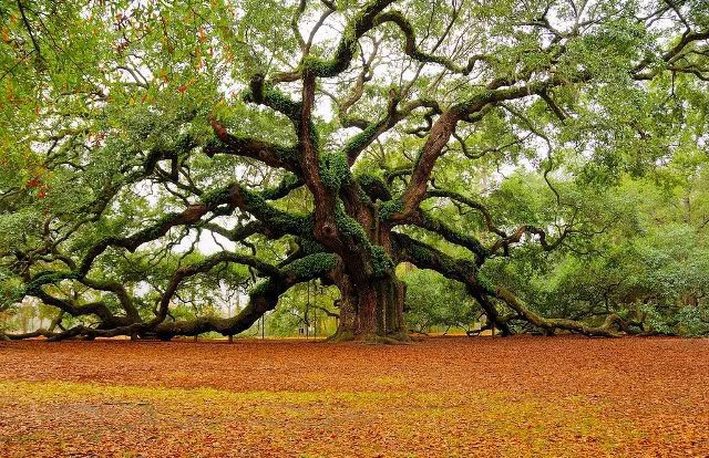

It is at the end of the rope woven by the father that the child starts to weave his own. - Fon Proverb The first time I was invited to San Francisco‘s Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD), it was to deliver an invocation and prayer for the opening of Africa.Dot.Com-Drums to Digital, an exhibit exploring “the changing landscape of communication and connectivity in Africa today.” Because the exhibit set the stage for making the intellectual leap from drum communication to digital connectivity, I made it my responsibility to help the patrons make a personal connection to the subject. My strategy was to create a ritual experience that would conjure the emotions associated with connectivity and communication – especially between past, present and future. The ritual started with a simple question: “How many of you folks here have ancestors?” Within seconds, the room opened up, as one-by-one, two-by-two, the people smiled and silently recalled the ones who had gone before them. As they did, I voiced the obvious: “We all have ancestors! It’s one of those great things all people have in common.” In spite of our staggering diversity, all people share a collective consciousness, a consciousness that is wrapped in the consciousness of somebody who lived before us. Think about it; your physical features, genetic traits, even your emotional dispositions are passed down from one generation to the next. For this reason, the Yorùbá say “no matter how far a river flows, it never forgets its source.” cudjoibeji“By protecting and celebrating the material, moral and intellectual property of our ancestors we perpetuate the link between our heritage and that of humankind, between the times of our ancestors and that of future generations.[1] Africatown represents a prime example of sustaining cultural heritage. This small neighborhood in Mobile, Alabama, was founded by the people who arrived on the infamous Clotilda, the last documented slave ship to reach the United States. On Sunday July 8, 1860—52 years after the United States had abolished slavery —the Clotilda sailed into Mobile Bay with 110 African men, women, and children between the ages of 5 and 23 on board. The majority of those Africans were Yorùbá of the Isha sub-group, who had been captured in a dawn raid led by Ghezo, the king of Dahomey, in the Banté region of Benin.[2] Cudjo Lewis – born Oluwale Kossola (ca. 1841-1935) was a founder of Africatown and at the time of his death, was the last survivor of the Clotilda. Africatown (like Allensworth, CA and Oyotunji, SC) represents one of many bright stars in the constellation of Yorùbá cultural heritage. According to Yorùbá tradition, heaven is our home. The Yorùbá Arch Divinity, Obatala descended with the Calabash of Creation and established life on Earth at the Holy City, Ifè. From there, people dispersed into the four directions. Ogundele Fagbemi, the most senior Babaláwo in the USA once told it to me this way; “We are not separate people trying to come together for the first time. We started out together and spread out. So now it’s only a question of coming home.” Some of the major stars of the Yorùbá/Fon cultural constellation include: Lukumi (Cuba) Nago (Haiti) Rada (Haiti) Shango (Trinidad, Grenada) Ijexa, Gege, Nago (Brazil) Saro (Sierra Leone) Ga (Ghana) Ewe (Ghana, Togo, Benin) Fon (Togo, Benin) Ìdáìsà (Benin) Ife (Togo) Aku (Liberia) Aguda (Cuban & Brazilians who returned to Nigeria) Ife, Ijebu, Anago, Awori, Ondo, Ekiti, Oyo, Kogi, Ijesa, Ketu, Egba, Egbado, Sabe, Popo, Ila, etc. (Nigeria) ere Most importantly, each of the cultural groups mentioned above represents a lineage, whose existence is perpetuated generation after generation. Here, time is discontinuous, and space is continuously rebuilt through ritual and rebirth. The historical continuum that links the different Yorùbá groups is a space-time circle, always mobile, dynamic and in accordance with the Fon creation principle, expressed as Ayido Xuédo, the rainbow serpent that is at once swallowing itself tail first and emerging from its own mouth. This principle, expressed by the Yorùbá as Olodumare, incarnates at once the concepts of movement, permanence and continuity. The Yorùbá cultural constellation is, in this sense, a living entity. Its history is communicated in a language of signs, symbols and material culture. Collectively, the greater Yorùbá history is reconstructed through a combination of micro-histories, obscure local histories, where meaning is reflected through the decoding of symbols, the study of settlement patterns, family formations, economic/social infrastructure, worship techniques, and the mystical links existing between the people, their sacred arts and the local environment (trees, rituals, sacred places and temples). Everyday, the international Yorùbá community is taking more responsibility to protect our heritage at the global level. As the wisdom, relevancy and potency of obafemitraditional Yorùbá religion continues to gain traction all over the world, more people are recognizing in Yorùbá heritage the creative genius of a diverse people versed in the art of living. Said recognition offers a strong base for sustainable development and a renewed hope for dialogue between men and cultures. To learn more about what you can do to promote and sustain cultural heritage, contact: Obafemi Origunwa 510.485.2336 | ObafemiO.com | Obafemi@yahoo.com [1] Unesco. [2] Encyclopedia of Alabama: http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/face/Article.jsp?id=h-1402 May 3, 2009  While Èsù’s character is synonymous with impetuous motion and perpetual change, other òrìsàs epitomize unwavering stillness and abiding calm. One such deity is Obàtalà (Lisa, Òrìsànlá, Oxala). As the Yorùbá Arch Divinity, Obàtalà is the venerable father, whose wisdom fills the devotee with aristocratic poise and regal presence. From his oriki we get a glance of Obàtalà’s austerity: He is patient. He is silent. Without anger he pronounces his judgment. Here it’s important to note that we all enjoy some degree of Obàtalà consciousness. For example, recall a time when you had to demonstrate deep cool. Maybe you were confronted by an emotionally intense situation, like natural childbirth or attending a loved one’s funeral. Perhaps you were facing a fast-approaching deadline or you were about to present some very important information. Think about what it was like to be “at the eye of the storm”, where, in spite of the fact that everything around you was spinning, you found yourself in a state of deep stillness. This is a flash of Obàtalà consciousness. After many years of practice and experience, a wise person comes to understand the virtue of stillness. Yoruba traditional thought reminds us that “What an elder sees sitting down a youngster cannot see standing up.” Like his elder brother Obàtalà, Orúnmìlà is also notoriously serene. In a verse of the Holy Odù Ifá called Ogbe Ogunda Orúnmìlà teaches us that when he is offended he waits three years before responding, giving the offender ample time to rectify the situation. Even when he does decide to respond his motion is as slow as the snail, even though he has as many feet as the millipede, who has 200 pairs of feet but still moves slowly and gracefully. Orúnmìlà says that if a stone obstructs his path, he coils up beside the stone until falling leaves and branches fall, forming a bridge for him to cross. Likewise, if a tree falls in his path, Orúnmìlà says he will wait for it to decompose before continuing the journey. Ogbe Ogunda says; An uncontrolled temper does not create anything for anyone. Patience is the father of existence. A patient person has everything. She will reach a ripe old age. He will enjoy a healthy life. And she will enjoy life thoroughly, Like a person tasting honey. Once there was a poor man who had only a single set of ragged clothes, lived in a ragged house and struggled daily to feed himself and his wife. The depth of their deficiency, however, was the absence of children. One day, God answered their prayers and sent the unfortunate couple patience, child and money. On the journey to the poor man’s house, patience, child and money reached the river bank. Patience started across, slowly but surely. Meanwhile, the water was too cold for money and too deep for child. Money refused to carry child on the grounds that wealth is senior to progeny. While they stood there quarreling, patience quietly returned and carried them across, one by one. Eventually, the three travelers arrived at the poor man’s home. They explained that Olódùmarè had sent them as an answer to their prayers. After five days with the poor man he and his wife must pick one and send the other two back to heaven. The poor man consulted his wife. “If we have a child without money how can we feed it?” she asked. “And patience after all, is worthless. Pick money.” Next he consulted his friend, Abinuku. Unbeknownst to the poor man, Abiniku was secretly jealous of his friend. He wished that the three travelers had visited his house instead. So he deliberately gave the poor man what he considered bad advice. He said, “Your wife is right. If you pick a child without money you cannot feed it. But at the same time, money minus a child means your estate will goes to strangers upon your death. So chose patience.” The poor man agreed with friend’s advice. At the end of five days, his wife was disappointed to find money and child packing their belongings and bidding the poor couple farewell, while patience was settling in to live with the family. The two travelers again arrived at the river bank. Again the water was too cold for money and too deep for child. Once again, money refused to carry child on the grounds that wealth is senior to progeny. Once again they stood there quarreling. But without patience there to ferry them across, they saw no other option but to return to the house of the poor man to seek refuge. Later that evening, you can imagine his wife’s elation to see money and child approaching the house again. She and her husband were happy to take them into their family to settle in alongside patience. This is why the Yoruba say that one who has patience has everything. Make time this week to create a plan for deepening your well of patience and forbearance. Good things will soon follow. January 26, 2009 "It is when the young awo becomes knowledgeable that he becomes a threat to his elders, according to proverbial wisdom. But more urgently, it is when you become committed to living the medicine that you become a threat to your peers and contemporaries.

When you stop talking about changing and you actually start living the medicine, then you will see the social disease that surrounds you more clearly. Some will disappear without a trace. Others will make petty charges and challenges. Still others will be like wolves in sheep's clothing, who smile and grin and offer platitudes laced with sabotage and deception. Know that all of this is par for the course. Do not allow yourself to be discouraged. Ifa teaches us that there are three categories of people; the achievers, the supporters and the bystanders. As long as you dedicate yourself to those three personality types, you will be more likely to thrive.

You never know how it's going to end. No matter how many relationships you start, you never seem to hone the ability to accurately predict the way it ends. Even the idea of anticipating the end of a relationship is a bit unsavory, kind of like knowing the date of your own death. Who really wants to know?

At the same time, however, consider this: What if you actually started the relationship with a happy ending in mind? It would require that you give serious consideration to your elderly years, your desired living conditions and yes, your eventual transition to the ancestral realm. There is a great movie called Big Fish. If you have never seen it, be sure to check it out asap. It's a film about an ordinary man with an extraordinary appreciation for storytelling. Like a child who enjoys a vivid imagination, he lives the story of his life with great enthusiasm and a sense of awe. And in the end, imagination and reality converge at the time of his death. The end is inevitable. Nothing endures forever. The question, however, is How do you WANT it to end? In other words, define happily ever after. Invest a little imagination into your vision of a happy ending so that you can feel the inspiration drawing you closer to it everyday. How do you really want to spend your golden years? Is the person you're with today part of the picture? Does your partner really have what it takes to be a main character in the amazing story of your life? If so, then tell that story with vivid detail and imagination. If not, then let them go. Don't cast them aside, mind you. But remember what the opening lines of the Holy Odu IrosunIwori: Let us do things with joy Those who wish to go, let them go Those who wish to stay, let them stay The journey of life is an amazing, epic tale of adventure, challenges and opportunities. The way you show up in that story will ultimately become your legacy. It is your responsibility to populate that story with the right people, who are really capable of adding value to your final contribution. In order to heal your relationship - and more importantly, your life - heal your story. Then live the medicine that will heal your life and the lives of those you're destined to serve.

"People don't talk about mastery much these days. But when I started the journey, my teachers always referred to the elevated masters, who had reached a deep understanding and perfection of the practice. Living the medicine, however, is not about the mastery of external disciplines. Living the medicine means mastering the mystery of your identity. Learn more at the Orisa Lifestyle & Mental Health Retreat" Obafemi Origunwa, MA | www.ObafemiO.com |

Live the MedicineObafemi Origunwa, MAThought leader, Ifa priest and author of four definitive books, Obafemi Origunwa inspires metamorphosis through living the medicine that will heal your life and heal the lives of the people you're destined to serve.

Raise Awareness

Internalize Principles

Embody Truth

|