Sacred Arts, Passion & Inner Vision

In high school, my best friend, Darrell was able to visualise math. He literally saw numbers. This allowed him to solve complex equations and combine very large numeric values practically on sight. Since I was “mathematically challenged”, his effortless talent for numbers both fascinated and baffled me. Nothing in my mind would allow me to grasp how someone could understand – let alone enjoy – math the way he did. It seemed quite natural to Darrell. I remember asking him the secret. He told me that when he looked at an equation, a kind of a kalaidescope image appeared in his mind. So, whereas 10 X 10 was just 100 to me, to him, it took on a particular shape; he described it as something like 10 concentric rings divided into ten segments. When I consider the infinite variety of images potentially associated with computations, it’s easy for me to understand how Darrell’s unique vision fueled his passion for numbers.

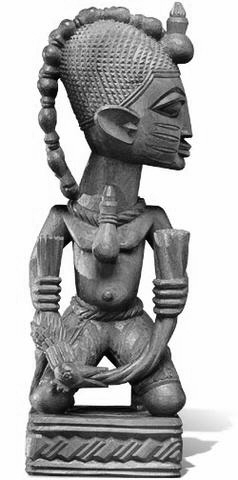

Similarly, the world-reknown Yorùbá carver, Lamidi Fakeye once asked an interviewer in Nigeria, “When you look at a block of wood what do you see?” “A dead tree”, came the reply. “Pity,” he said , “I would imagine you were more creative than that…I see a soul looking for a body to inhabit; seeking to clothe itself in a form which is life.” Fakeye’s lucid inner vision is anything but one individual’s personal experience, however. It reflects millenia of collective consciousness and specialized training. Babatunde Lawal tells us that, among the Yorùbá of Nigeria and the Republic of Benin, even from the moment of procreation and inception, life is imbued with artistic expression. To the Yorùbá, the human body is the handiwork of the Arch Divinity and heavenly sculptorObatala. Hence the prayer for an expectant mother: “Ki Orisa ya ona ire ko ni”(May the Orisa [Obatala] fashion for us a good work of art).

Lawal goes on to tell us that the word aworan commonly refers to any two- or three-dimensional representation, ranging from the naturalistic to the stylized. A contraction of a (that which), wo (to look at), and ranti (to recall), aworan is mnemonic in nature, identifying a work of art as a construct specially crafted to appeal to the eyes, relate a representation to its subject, and, at the same time, convey messages that may have aesthetic, social, political, or spiritual import. The same is true of drumming, dancing – even math! All aspects of life are infused with a coded language, a deep truth, whose objective is to harness the power of the unseen realm and transport into the visible realm. In other words, the body is a vehicle through which the spirit manifests, enabling an individual to have iwa (physical existence) in the visible world. Iwadenotes not only the fact of being but also the distinctive quality or character of a person. This is the essence of spirit possession, which is a defining characteristic of African creative expression. “Ritual contact with divinity,” writes Robert Farris Thompson “underscores the religious aspirations of the Yorùbá. To become possessed by the spirit of a Yorùbá deity, which is a formal goal of the religion, is to… capture numinous flowing force within one’s body.” Quoting Araba Ekó, Lagos, Nigeria, Thompson continues:

The gods have “inner” or spiritual eyes (ojú inú) with which to see the world of heaven and “outside” eyes (ojú ode) with which to view the world of men and women. When a person comes under the influence of a spirit, his ordinary eyes swell to accommodate the inner eyes, the eyes of the god. He will then look very broadly across the whole of all the devotees, he will open his eyes abnormally.

Within the Yorùbá tradition, when a devotee becomes possessed, people come close, so as to be seen by the divinity and learn what messages it brings from the ancestral realm. It suggests that to be seen by the divinity is to the blessed. Thus contained, controlled, and incorporated into the performance of sacred arts, the powers of the spiritual world can be accessed and utilized with a cursory glance. Hindu philosophy speaks of darshan, loosely translated as auspicious seeing or “auspicious sight.” In similar fashion, the Holy Odù Iwori Méjì underscores the idea of auspicious sight very completely:

He who a person follows out

Is he with whom he ought to return home

For he whom a dog follows to a place

Is he with whom the dog returns home

These were the declarations of Ifá to Eleji Iwori

The one who shall take intense look at his Akapo (disciple)

He was advised to offer ebo

And he complied

Ifá, please take an intense and favorable look at me

Éjì Iwori, I am truly your child

If you take an intense look at one

Such person is guaranteed with financial success

Éjì Iwori, I am truly your child

If you take an intense look at one

Such person is guaranteed the blessing of a good spouse

Éjì Iwori, I am truly your child

If you take an intense look at one

Such a person is guaranteed the blessing of good children

Éjì Iwori, I am truly your child

If you take an intense look at one

Such a person is guaranteed victory over adversaries

Éjì Iwori, I am truly your child

If you take an intense look at one

Such a person is blessed with all good things

Éjì Iwori, I am truly your child

Éjì Iwori.

The divinities have the ability to impart blessings by way of “auspicious seeing” because they exist on a higher plane, in the realm of pure, unfettered power to make things manifest. Much like a well-seasoned artist, they can see what is yet to exist and bring it into being. What is important to note here is that each of us was born with auspicious seeing. My friend Darrell, for example, was born with the ability to see numbers and recall images. Likewise, a carver stares intently at a block of wood while conjuring up the relevant schema from his pictorial memory. Thus, the term aworan signifies much more than an image that recalls the subject. It also alludes to the creative process, especially the preliminary contemplation (a-wo) of the raw material and the pictorial memory (iranti) necessary for visualizing and objectifying the subject. I invite you to make time today to visualize your life as you would like it to be. In your mind’s eye, envision financial success, a loving spouse, good children, victory and all other elements of the good, meaningful life.

Similarly, the world-reknown Yorùbá carver, Lamidi Fakeye once asked an interviewer in Nigeria, “When you look at a block of wood what do you see?” “A dead tree”, came the reply. “Pity,” he said , “I would imagine you were more creative than that…I see a soul looking for a body to inhabit; seeking to clothe itself in a form which is life.” Fakeye’s lucid inner vision is anything but one individual’s personal experience, however. It reflects millenia of collective consciousness and specialized training. Babatunde Lawal tells us that, among the Yorùbá of Nigeria and the Republic of Benin, even from the moment of procreation and inception, life is imbued with artistic expression. To the Yorùbá, the human body is the handiwork of the Arch Divinity and heavenly sculptorObatala. Hence the prayer for an expectant mother: “Ki Orisa ya ona ire ko ni”(May the Orisa [Obatala] fashion for us a good work of art).

Lawal goes on to tell us that the word aworan commonly refers to any two- or three-dimensional representation, ranging from the naturalistic to the stylized. A contraction of a (that which), wo (to look at), and ranti (to recall), aworan is mnemonic in nature, identifying a work of art as a construct specially crafted to appeal to the eyes, relate a representation to its subject, and, at the same time, convey messages that may have aesthetic, social, political, or spiritual import. The same is true of drumming, dancing – even math! All aspects of life are infused with a coded language, a deep truth, whose objective is to harness the power of the unseen realm and transport into the visible realm. In other words, the body is a vehicle through which the spirit manifests, enabling an individual to have iwa (physical existence) in the visible world. Iwadenotes not only the fact of being but also the distinctive quality or character of a person. This is the essence of spirit possession, which is a defining characteristic of African creative expression. “Ritual contact with divinity,” writes Robert Farris Thompson “underscores the religious aspirations of the Yorùbá. To become possessed by the spirit of a Yorùbá deity, which is a formal goal of the religion, is to… capture numinous flowing force within one’s body.” Quoting Araba Ekó, Lagos, Nigeria, Thompson continues:

The gods have “inner” or spiritual eyes (ojú inú) with which to see the world of heaven and “outside” eyes (ojú ode) with which to view the world of men and women. When a person comes under the influence of a spirit, his ordinary eyes swell to accommodate the inner eyes, the eyes of the god. He will then look very broadly across the whole of all the devotees, he will open his eyes abnormally.

Within the Yorùbá tradition, when a devotee becomes possessed, people come close, so as to be seen by the divinity and learn what messages it brings from the ancestral realm. It suggests that to be seen by the divinity is to the blessed. Thus contained, controlled, and incorporated into the performance of sacred arts, the powers of the spiritual world can be accessed and utilized with a cursory glance. Hindu philosophy speaks of darshan, loosely translated as auspicious seeing or “auspicious sight.” In similar fashion, the Holy Odù Iwori Méjì underscores the idea of auspicious sight very completely:

He who a person follows out

Is he with whom he ought to return home

For he whom a dog follows to a place

Is he with whom the dog returns home

These were the declarations of Ifá to Eleji Iwori

The one who shall take intense look at his Akapo (disciple)

He was advised to offer ebo

And he complied

Ifá, please take an intense and favorable look at me

Éjì Iwori, I am truly your child

If you take an intense look at one

Such person is guaranteed with financial success

Éjì Iwori, I am truly your child

If you take an intense look at one

Such person is guaranteed the blessing of a good spouse

Éjì Iwori, I am truly your child

If you take an intense look at one

Such a person is guaranteed the blessing of good children

Éjì Iwori, I am truly your child

If you take an intense look at one

Such a person is guaranteed victory over adversaries

Éjì Iwori, I am truly your child

If you take an intense look at one

Such a person is blessed with all good things

Éjì Iwori, I am truly your child

Éjì Iwori.

The divinities have the ability to impart blessings by way of “auspicious seeing” because they exist on a higher plane, in the realm of pure, unfettered power to make things manifest. Much like a well-seasoned artist, they can see what is yet to exist and bring it into being. What is important to note here is that each of us was born with auspicious seeing. My friend Darrell, for example, was born with the ability to see numbers and recall images. Likewise, a carver stares intently at a block of wood while conjuring up the relevant schema from his pictorial memory. Thus, the term aworan signifies much more than an image that recalls the subject. It also alludes to the creative process, especially the preliminary contemplation (a-wo) of the raw material and the pictorial memory (iranti) necessary for visualizing and objectifying the subject. I invite you to make time today to visualize your life as you would like it to be. In your mind’s eye, envision financial success, a loving spouse, good children, victory and all other elements of the good, meaningful life.